Photo: Charlie Musselwhite by Rory Doyle

Interview with Charlie Musselwhite, Legendary Bluesman

By Martine Ehrenclou

Grammy Award-winner, multi Grammy nominee, 13-time Blues Music Award-winner, Charlie Musselwhite is a living legend of the blues and in the truest sense of the word, a bluesman. World renowned as a harmonica master, truth-telling vocalist, songwriter and guitarist, Musselwhite has released nearly 40 albums over his six-decade career, proving that music only gets better with age.

Charlie Musselwhite’s life story is a fascinating one. Born into a blue collar family in Kosciusko, Mississippi, he was raised by a single mother who moved the family to Memphis. As a teenager, Charlie worked as a ditch digger, concrete layer and moonshine runner. Fascinated by the blues, Musselwhite began playing guitar and harmonica and soon befriended Memphis’ veteran bluesmen like Furry Lewis, Will Shade and Gus Cannon.

Musselwhite later moved to Chicago in the early 1960s. He drove an exterminator truck by day and hung out in Chicago’s South Side blues clubs by night. Sharing an apartment with blues harmonica giant Big Joe Williams, he befriended other blues icons such as Little Walter, Sonny Boy Williamson, Howlin’ Wolf and more. Before long, he was sitting in at clubs with Muddy Waters, Magic Sam, Earl Hooker, Jimmy Reed and others, amassing an impressive reputation. His first album Stand Back! Here Comes Charlie Musselwhite’s South Side Band launched his career and is regarded as one of the most influential blues recordings in history.

A groundbreaking recording artist firmly rooted in the blues, Musselwhite has also been featured on recordings by Tom Waits, Eddie Vedder, Ben Harper, John Lee Hooker, Bonnie Raitt, The Blind Boys of Alabama, INXS, Hot Tuna, Cyndi Lauper, George Thorogood and many others. In 2020, Musselwhite teamed up with Elvin Bishop and released 100 Years of Blues via Alligator Records, which earned a Grammy nomination and Blues Music Award.

Inducted into The Blues Foundation’s Blues Hall of Fame in 2010, Charlie’s recordings include straight blues with elements of jazz, gospel, Tex-Mex, Cuban and more. With his new album, Mississippi Son out on Alligator Records, he’s returned to his roots and the blues he fell in love with, recording stripped down, emotionally raw performances that deliver the truth of the blues.

Charlie Musselwhite spoke to me by phone from his home in Clarksdale, Mississippi.

Martine: Tell me about your song “Remembering Big Joe” on Mississippi Son.

Charlie: When I got to Chicago in 1962 I was 18 and I started rooming with Big Joe Williams. We were staying in the basement underneath the Jazz Record Mart at the corner of State and Grand. That was great because here’s this old time blues singer, one of the last of the itinerate blues singers. He played a nine string guitar and he wrote, “Baby, Please Don’t Go.” He knew everybody. He knew Robert Johnson and Charlie Patton and all the guys from way back. He was still working and just a tough old guy. We were really good friends for the rest of his life. After he died, a friend of mine in Mississippi inherited one of his guitars and happened to come through Clarksdale with it. I said, ‘Let me see that.’ I just started playing it. It was just a spontaneous song that I played remembering Big Joe playing his guitar.

Martine: You had no intention of becoming a professional musician until you met Big Joe Williams, is that right?

Photo: Charlie Musselwhite by Rory Doyle

Charlie: Well, it was a little after that. I had learned how to play blues in Memphis when I was growing up there, simply because I felt like I just had to play it. I loved it so much and it felt so good to me to listen to it. And I figured it’d feel even better to play your own blues. And I liked all kinds of music, but blues sounded like how I felt.

I got to know a lot of the old time blues guys around Memphis, around Beale Street, and learned from them. I didn’t know at the time that I was preparing myself for a career, or I’d have paid a lot more attention. I was just having fun. I didn’t have a dream to be on stage or nothing. But when I got to Chicago, I discovered the whole blues scene and started going to all the clubs and got to know Muddy Waters and Little Walter and Howlin’ Wolf. I wasn’t going around asking to sit in, I didn’t tell them I played. I was happy to just be there, hanging out, listening to the real-deal live blues. And coming from Memphis, I already knew how to drink. So I just fit right in. (Laughs)

They just thought I was a fan. I’d request tunes and stuff. But one time a waitress I’d gotten to know told Muddy, “You ought to hear Charlie play harmonica.” And that changed everything, because he insisted I sit in, and the other musicians that were hanging out with Muddy heard me playing and they offered me gigs. And boy, they got my attention. You going to pay me to play? All right! (Laughs) That was my ticket out of the factory.

Martine: Tell me about playing with Muddy Waters, Howlin Wolf and all of them. It sounds so exciting.

Charlie: It really was exciting at the time. And as the years go by, it just seems to get bigger somehow. (Laughs) They were real encouraging to me and pushed me to play and sing. They were flattered that I would come alone to these real rough little clubs where they played. I’d hang out ‘till the place closed many nights, and they thought I was really something. (Laughs) They would introduce me to other people and always say, “Now, Charlie, he’s from down home.” That to them, was special. I just got to know everybody. They were real welcoming and I started playing in all the little clubs and even out on Maxwell Street, and my name got around, and one thing led to another, and I ended up doing some recordings. And then Sam Charters from Vanguard Records asked me if I wanted to make an album. They gave me three hours to cut that record. I said, “Okay, let’s go.” (Laughs) It’s never been out of print, and it put me on the road and gave me a career. I was 22 when it came out.

Martine: That must have really changed your life.

Charlie: It did. I’d been working these small clubs in Chicago and working in factories. A lot of the musicians had day jobs, unless you were a Muddy Waters or Howlin’ Wolf who had 45s coming out all the time and toured all around. They didn’t have to have a day job, but most of the other guys did, because those little clubs didn’t generate enough money to pay enough to live on. But when I got to the West Coast, when that album came out, they started playing it on the underground radio. And suddenly, I’m getting all these calls to come play, and they’re offering me way better money I ever heard of in Chicago. So, that’s why I ended up on the West Coast and it all worked out.

Martine: It sure did. (Laughs) How did you originally get into playing harmonica?

Charlie: I always had harmonicas. I had been going around Memphis, looking for old blues 78s, and I found a lot of them in junk stores and used furniture stores. I really liked the way the first Sonny Boy Williamson sounded, and some other harmonica players too.

To me playing the harmonica, it sounds like singing without words, it’s real voice-like. And I was thinking to myself, you’ve got a harmonica and you like the way it sounds playing the blues, then play your own blues. So, I’d take my harmonica, go out in the woods or down by the creek, and I just started teaching myself at first. Actually, it’s the only instrument you cannot see how it’s played, so you pretty much have to teach yourself.

Photo: Charlie Musselwhite by Rory Doyle

Martine: That’s so interesting. I had never thought of that before.

Charlie: Yeah. When you’re fretting the strings (on guitar) or playing the piano or beating on the drums, your hands are always in use and you can see what’s going on.

Martine: So, how did you teach yourself to play then?

Charlie: I just looked for the tones that sounded right to me, and just started getting the lay of the land, you might say. The patterns on the harmonica. I didn’t know in the beginning that you could play in different keys on one harmonica.

Martine: I didn’t know that either. I know little about the harmonica, just listening to you and a few others, and yours obviously sounds incredible.

Charlie: Thank you. Well, I admire your taste. (Laughs)

Martine: (Laughs) You were good friends with John Lee Hooker, and he was your best man at your wedding. Can you tell me about your friendship with him?

Charlie: John lived in Detroit and I was in Chicago, but he would come to Chicago to play regularly, and I’d make it a point to be there to hear him and see him. First time I met him, we just became instant friends and we stayed friends ‘till the end. I mean, he’s not here now, but I’m still his friend. And we were real close. I would stay at his house sometimes. And I recorded on a lot of his albums and he recorded on one of mine. He was just a real good, generous guy. Great sense of humor. We had a lot of fun together.

Martine: You’re quoted as saying that besides all blues, that you’ve always been a fan of music that’s from the heart.

Charlie: Yeah, that’s true. On the album there’s a country tune by Ralph Stanley, and I kind of blues-ed it up because I really liked his lyrics, and the same with the Guy Clark tune–he’s more of a folk country guy. And I blues-ed that one up. When I was collecting 78s as a kid in Memphis, I discovered a lot of music that seemed to be from the heart the way I think of blues, like flamenco, Greek music and gypsy music.

I came to the conclusion that every culture around the world has this music of lament. No matter where you go in the world, there’s some guy on a corner singing about, my baby left me. (Laughs) It’s from the heart. You can feel it, you can recognize it. Just like when people hear blues in another culture, they might not know what I’m singing about, but they recognize the feeling. When I’ve met musicians in other cultures, we might not be able to speak to each other, but we can play together because we’re playing from the same place, from the heart.

It’s fascinating to me how I can blend the blues that I know with another guy playing some strange instrument in another culture. And it just seems to make sense. It just seems to fall together effortlessly.

Martine: What music do you listen to now? Do you listen to blues?

Charlie: I like all kinds, as long as it feels real to me and not contrived. I like old Hillbilly music and gospel music, blues and good jazz, not elevator jazz. Some of these guys, it seems like to them, it’s all about technique, and they’ll play thousands of notes and just play furiously. And I’m thinking to myself, well, that’s interesting, but where’s the music? It reminds me of somebody that has a huge vocabulary, but nothing to say. It’s just like a formula. They just crank it out and it doesn’t have any depth or substance. But if they’re making a buck at it, more power to you. (Laughs)

Martine: (Laughs) You’ve played with B.B. King, Bo Diddley, Eric Clapton, Koko Taylor, Jimmie Vaughan—

Charlie: Cyndi Lauper, Tom Waits, Ben Harper, and even Eliades Ochoa and Cuarteto Patria from Cuba. We toured together. Patria, he’s the guy that played guitar with Buena Vista Social Club. But in my opinion, his band, the Cuarteto Patria, is way better than the Buena Vista Social Club.

Martine: You must have had a blast touring with them.

Charlie: I call him the Muddy Waters of Cuba. I mean, these guys are real down home. They wore cowboy boots. In Havana they have the big ruffles shirts and the pants up to their armpits. (Laughs) They were so easy for me to play with. They didn’t know anything about blues, but we were both playing from the heart, and we just had a great time recording together and touring together. They were on my album called Continental Drifter.

When I was working with Cyndi Lauper, she put out a blues album called Memphis Blues. When we went on the road, she wanted to do her hits too. Like “Girls Just Want to Have Fun.” Suddenly that tune had a harmonica solo in it. She was a really interesting woman to tour with and play with, and quite the musician herself. It was a fun challenge for me to play blues harmonica with rock songs. It was a blast.

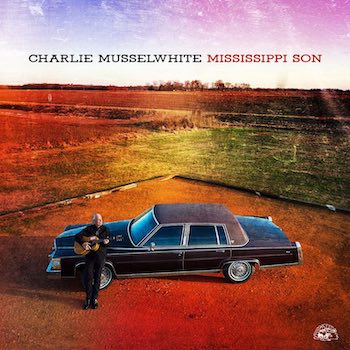

Martine: Mississippi Son has a very cool album cover.

Charlie: That’s my ‘89 Cadillac on there. It’s got a big old engine and loves the road. Mostly I just tool around the Delta in it.

Martine: I promised to keep the interview to 30 minutes so I want to respect that.

Charlie: Seems like five.

Martine: It does to me too. It’s been great to talk with you. So interesting. I’ve really enjoyed it.

Charlie: We’ll do it again sometime. A real pleasure for me too. I look forward to it. Stay safe.

Charlie Musselwhite website

Listen to Charlie Musselwhite’s “Crawling King Snake” HERE

Great Article. I have been listening to Mr Musselwhite since his days in Chicago when he played with many of the South Chicago greats- what’s cool about Charlie is he is so down to earth- Saw him last summer at a festival and was mesmerized. Thank you Charlie Musselwhite for sharing you great talents!

What an interesting road Charlie has followed. Enjoyed learning his life story — everyone has that, and his is pretty darn cool!

Big admiration for this wonderful musician!

Thank you, both.

Such a good interview! Been listening to Charlie since the early seventies. Really loved his first album, Stand Back, with the legendary Harvey Mandel on guitar! Another favorite is Continental Divide with Cuban musicians. Love all the other albums, too! Great sample from his new album, also.

Seen charlie in Orono, Maine…fantastic….great interview….keep the blues alive..

Great interview with one of the living legends.