Woody Guthrie

By Jay Luster

Fifty-five years after his death in 1967, Woody Guthrie’s legacy, musically and politically, continues to live on. Born into a well-to-do Okemah, Oklahoma family in July of 1912, Guthrie, for the first years of his life lived in comfort. In the mid-1920’s, his father Charles lost everything in bad real estate deals.

By the age of 14, young Woodrow Wilson Guthrie found himself busking on the street for spare change. As the Great Depression set in, and the drought driven Dust Bowl destroyed farms and towns, many people in the region, like his dad a few years earlier, lost everything. With little more than the clothes on their backs, they began migrating westward to California where they believed the skies were clear, the farmland was fertile, and the weather pleasant. Guthrie headed west as well.

The startling contrast between the haves, and the have-nots during the Depression inflamed Guthrie’s egalitarian sensibilities, and he became an avowed socialist. As he hitchhiked, and hobo’d his way across the USA, he wrote, and sang his songs to gatherings of migrants in meeting houses, and in the CCC work camps which had sprouted up as part of FDR’s new deal.

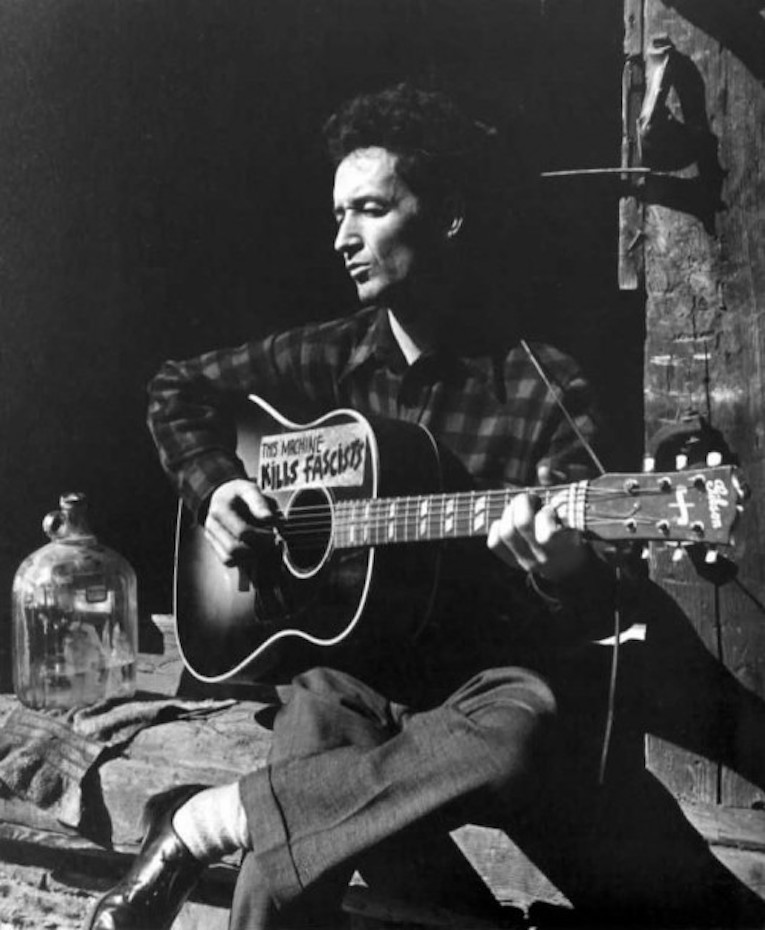

The songs he shared with his audience invited people to form and join unions, demanded equality between the races, encouraged environmentalism, and raged against fascism. As an answer to Hitler’s atrocities, he wrote passionate songs and played them on a guitar emblazoned with the slogan, “This Machine Kills Fascists.”

In 1940, Guthrie released his first album, and recorded his songs for Alan Lomax for the National Archives. Lomax, famed for documenting such artists as Robert Johnson, also recorded another black blues musician named Huddie Ledbetter. Ledbetter, better known as Leadbelly, traveled and recorded with Guthrie in 1940 and 1941. One of the songs they performed together was Guthrie’s, rather clever “We Shall Be Free.” While not exactly anti-religious, its lyrics humorously but quite scathingly unmask phony preachers.

Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly

“Preacher an’ a rooster had a terr’ble fight

Preacher knocked the rooster clean out o’ sight

Preacher told the rooster that’ll be all right

Meet ya at the hen house tomorrow night,”

In the rural places where Guthrie plied his trade, religion and patriotism go hand-in-glove. Words like this make it easy to see why people of his era whispered he might be a communist.

While it’s true socialism was his creed, shining a light into the darkened places hypocrites hid seems to have been just as important to him. He wrote a song about “Pretty Boy Floyd” which attempted to show how the outlaw was made by circumstance, rather than being born bad.

He painted Floyd as a sort of Robin Hood figure, who gave much of his ill-gotten gains to the poor. While that part of the story is true, Guthrie didn’t mention the ten people Floyd killed during his crime spree. By today’s standards that might be an unforgivable oversight, however, when it was recorded in 1939, many of the bank robbing criminals of the day were seen as swashbuckling heroes by a populace still reeling from the Depression. John Dillinger, Floyd, and many others from the public enemy era were popularly believed to be striking back at the fat cats who were happily ignoring the plight of their own countrymen.

Eventually, the government also began suspecting he was a communist, but no evidence has ever come forward to attach him directly to it. Unlike Lucille Ball, and others who actually had registered as communists in their voting records, no such documents exist for Guthrie. However, his politics were an ever-present part of his life, and art. He was a socialist, who would have been happy to upend American capitalism for the more equitable system he imagined. Nonetheless, with quips like, “I ain’t a Communist necessarily, but I have been in the red all my life,” it’s easy to see how the paranoia of the red scare era got him blacklisted.

Still, it is music that defines him, and his catalog is studded throughout with great songs, some of which are just as pertinent today as they were when he was actively recording. “John Henry,” is the tale of a black railroad worker fearing he was losing his livelihood to mechanization. His death while competing with the steam drill is still a salient metaphor of the human cost of progress.

“Do Re Mi,” his nickname for money, illustrates the welcome many Dust Bowl refugees received when they arrived in California. Despite what the destitute believed while laboriously crossing the Great Plains, Rocky Mountains, and western deserts, California’s economy was equally devastated by the Great Depression as everywhere else in America, and the world. Guthrie sang,

“California is a garden of Eden,

a paradise to live in or see,

But believe it or not you won’t find it so hot

If you ain’t got the do re mi”

His most famous song is “This Land Is Your Land,” which was written as a sort of answer to Irving Berlin’s “God Bless America.” That song, sung in a booming voice by operatic contralto Kate Smith, became popular during World War Two for its fist-pumping patriotism. However, to Woody’s ears, it sounded jingoistic and uninformed. While painting stunning, and vibrant pictures of the great American landscape, buried well down the lyric’s page, he remained his typically observant, and somewhat cynical self.

“One bright sunny morning in the shadow of the steeple

By the Relief Office I saw my people.

As they stood hungry, I stood there wondering if

God blessed America for me.

This land was made for you and me.”

In October of 1967, Woody Guthrie passed away from Huntington’s disease. He inherited the gene from his mother who suffered with it and died in 1930. Recognized in 1872 and named after James Huntington, the symptoms of this still incurable disease include a worsening of motor control, and brain function, and eventually death. He began showing symptoms in the 1950’s, and as the disease progressed along its predictable path, he was forced to retire.

The echoes of his music can be heard in songs like “Little Pink Houses” by John Mellencamp, “Nebraska” by Bruce Springsteen, and “The Way It Is” by Bruce Hornsby. He certainly wasn’t the first artist to stick a finger in the eye of religion, politics, and high society, but his shrewd observations, and Okie eloquence are just as inflammatory today as they were during the Dust Bowl migrations and Great Depression.

Woody Guthrie website

Leave A Comment